The Rhone River begins as clay-filled glacial run off high in the Swiss Alps. It winds its milky way across Switzerland, emptying its alluvial deposits at last into Lake Geneva and becoming, as Byron put it, “the blue rushing of the arrowy Rhone.” After curving through the foothills of the western Alps, The Rhone falls into a deep valley and turns south, running along the natural gap between the Cevennes Mountains and the French Alps toward the sea. For over 100 miles, the river follows the valley, hugging the eastern edge of the Cevennes, until, as the mountains fall away to the east and the west, it gathers its tributaries and fans out in a wide delta across the head of the Gulf of Lions, a small arm of the Mediterranean Sea.

Just before the Rhone splits into its two main channels, a last straggling arm of the Alps, the Alpilles, reaches westward, ending in a jumbled and rocky promontory a few miles from the river. This protective line of hills forms the base line of another delta, or triangle, with the upper lines created by the confluence of the Durrance and the Rhone. Within this secure and fertile triangle, succesive waves of ancient cultures established their communities and towns. Neolithic farmers arrived early in the seventh millennium BCE and dwelt in Arcadian simplicity until Bronze Age trading cultures, such as the Egyptian, Mycenean and Phonecian began to arrive in the second millenium BCE. Soon after this contact, Celtic tribes began to filter down the river from their European homeland north of Lake Geneva and conquered or integrated with the local culture to form a unique variety of Gallic Celt.

More than half a millennium before the birth of Christ, Greek traders built a fortress a few miles to the southwest of the old Celtic town, at the point where the Rhone forks. The trading center retained the AR of the Argonauts, the Greek heroes who originally sailed up the Rhone in search of Celtic gold. Arles, now known mostly for the visits of artists such as Van Gogh and Gaugin, began as a center of Greek culture in a barbarian paradise. The two communities mixed and grew into a larger city nestled in the protected delta north of the low range of volcanic hills, the Alpilles, near the present day town of St. Remy de Provence.

This Gallo-Greek city entered the Roman Empire in 46 BCE as the acquisition of Julius Caesar and received the name Glanum Livii.

Even its name, which must been have a Romanized version of some Gallo-Greek original, suggests the locality’s curious cultural and linguistic overlapping. The ambiguity of its literal meaning — Blue Swelling? — indicates a complex of similar homophones in the interrelated languages of the region which gave the town its name. A similar and possibly related method of homophonic symbolism within the Provencal language would evolve over time into the Green Language of the Troubadors.

Lost for almost 1700 years — Glanum disappeared from history in the generation after 270 CE and was not rediscovered until 1921 — this ancient city holds the key to the “underground stream,” the hidden mysteries of western esotericism. From Merlin to Nostradamus, from Parzival and the Holy Grail to Alchemy and the mystery of the cathedrals, from the origins of the Tarot cards to the Hebrew/Druidic /Arthurian cabala, most of the major currents flowing through the underground stream surface, or have their origin, within a few miles of the lost Roman city of Glanum.

Michael Nostradamus, the justly famous Seer of Provence, was born barely a mile from the Arch and the “pyramid,” as the Augustinian mausoleum was called in the 16th century. In Nostradamus’ time, these two monuments were all that remained above ground of Glanum. They are still standing today, stark reminders along the modern road into the Alpilles of the area’s ancient past.

Today’s visitor, standing under the two millennium old and still accoustically perfect Arch, gazes out on the excavations of Galnum and, if he is somewhat imaginative, can glimpse in his mind’s eye its antique glory. In the near distance, the discerning visitor will note an oddly shaped hill with a perfect round hole in its side. At the foot of this hill is the Monastry of St. Paul de Manseole, a 12th century church and cloister that now serves as a psychatric hospital. Van Gogh was commited there for a time before returning to Paris and committing suicide.

Nostradamus mentions this area in six of his enigmatic and prophetic quatrains and connects it with the symbolic term “mansol” and the discovery of a great “treasure” or secret. Perhaps Nostradamus foresaw the rediscovery of Glanum, full of Roman and Gallo-Greek treasures, in 1921, or perhaps the Seer of Provence was pointing to the secret of the western tradition, the holy grail of esotericism, still waiting to be discovered among it ruins. Perhaps, as Nostradamus seems to suggest, hidden near the pierced hill above the monastary of Manseole.

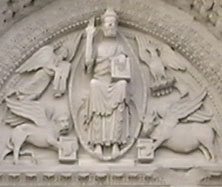

While a secret may remain hidden near Glanum, other clues to Provence’s unusual role in the history of western esotericism, including its Hebrew and Gnostic Christian roots, are hidden in plain sight. At Arles, which has often been called the soul of Provence, Greek and Roman relics abound. It is but a brief walk from the lovely Roman arena, equal in elegance if not in scale to Rome’s Coliseum, to the town square where a curious Romanesque church with a Gothic facade draws the attention of the serious hermetic student.

On sunny Sunday afternoons in the spring, the tour guides, explaining the images on the church front in terms of Hercules’ labors, compete with Hurdy-Gurdy music and the laughter of children. Few tourists ponder why a Christian Church in Provence uses the symbolism of ancient Greek myth, why its Saint is called Trophime, or Trophy, or even why Frederick Barbarossa, the Holy Roman Emperor in the late 12th century, chose Arles and St. Trophime for his coronation?

Attempting to answer these questions takes us deep into the heart of the Grail legends. The coronation of Frederick Barbarossa appears to be the key point of diffusion, the place and time where the Grail myths entered the story of King Arthur. As many other researcher have found, the Grail stories have much to do with a bloodline, the possible descendants of Jesus, hence the Green Language-esque pun of Sang Real, holy blood, out of San Graal, holy grail. Could the Trophey of St. Trophime be the Holy Grail? Even though the Hercules connection will remain obscure for a while — it is part of the deepest secret current of the underground stream — the area does present us with a solid and tangible link to the Holy Family.

Further to the southwest of Arles, where the western branch of the Rhone flows into the Mediterranean, stood an ancient Egyptian port and lighthouse, founded perhaps a thousand years before the Greek traders arrived. Called Ra by the Romans, this lighthouse and port marked the turning point in the channel that brought Egyptian merchant ships into the Rhone. Today, the ruins of the Egypto-Roman fortress of Ra lies a quarter mile beyond the breakwater off the small beach town of Les Stes. Maries de-le-Mer. However, this resort town, far off the beaten path at the end of a region of marshes and tidal flats called the Carmargue, holds the key to the mystery of what happened to the Holy Family after the death and possible resurrection/ascension of Jesus in Palestine.

Hebrew migration to the region around the mouth of the Rhone began with the era of Greek colonization spurred on by Alexander’s conquests in the east. The flow increased in the early 1st century of the Common Era under the encouragement of the Roman Emperor Octavius Augustus. After the destruction of Palestine in 70 CE, the flow became a torrent, and some of these Hebrew refugees were Christians.

Provencal tradition relates that soon after the events in Palestine, a shipload of Jesus’ relatives landed off the old Roman fort of Ra, near present day Les Stes. Maries de-la-Mer. By all accounts, the group included three Marys, covering the interwoven family of Jesus and John the Baptist. One of the three was Mary Magdalene, first witness to the resurrection and, by Gnostic accounts, Jesus’ foremost disciple and wife. Also included were Martha and Lazarus, members of the Magdalene’s family, a few local Romanized Jews including Maximinius and Sidonius, the blind man from Jericho, and, either welcoming them home or included miraculously as part of the ship’s company, Sarah the Egyptian. Traditon relates that the group spread out through Provence and preached the Good News with such success that by the time of the destruction of the Temple and the Diaspora, barely more than a generation later, Provence was at least partially converted to Christianity.

Two of the Marys, along with Sarah the Egyptian, remained in the sea-side village where they landed. When they died, around 50 CE, St. Trophime himself came from Arles to administer the last rites. The three were buried near a small oratory or chapel they had built in the center of the village. In the 9th century, a new church was built over the oratory and the graves, and, fortified, it became part of the town walls. Good King Rene, Count of Provence, excavated the old church looking for the Holy Grail. Having found the holy relics of the two Mary’s and Sarah, Rene built a lofty and imposing church of pinkish stone to house them. With its parapets, merlons, embrasures and internal fresh-water spring, the church acted as a virtually impregnable fortress designed to protect the town’s inhabitants from Moorish pirates and other marauders.

Stepping into the cool darkness of the church from the bright clear sunlight of Provence is to step back into another age, an age of faith that was at least superficially Christian, but actually illuminated, from within as it were, by the antiquity of its Goddess worship. Under the chancel, a flight of stairs leads down to the crypt, where King Rene found the bones of Sarah and the two Marys. Blackened by the candles of myriads of pilgrims, most of them Gypsies who come to pray before the statue of Sarah, the crypt envelopes the vistor with an atmosphere of dark and earthy mysteries. If this is Christianity, it’s far different from its more orthodox varieties. Here, the feminine is not excluded, but worshipped in a manner that is far more primitive than early Christianity.

This impression is heightened during the Fete of May, when the Gypsies gather to honor Saint Sarah and the two Marys. For several days prior to the festivals on the 24th and 25th of May, Gypsies from all over Provence, southern France and northern Italy pour into Les Stes Maries de-le-Mer, some still in their colorful horse-drawn caravans.

The three day festival begins by taking down the reliquaries of the two Marys from their chapel above the chancel. The relics are left on display while the statue of Sarah is brought up from the crypt, draped in many rich cloaks and paraded down to the sea.

The next day it is the two Marys’ turn to make the journey. Standing in a small blue boat, piled high with roses, and holding an urn full of healing balm, the two Marys travel on the shoulders of their four guardians down to the sea where they landed almost two millennium ago. In this simple ritual can be heard echoes of a Goddess tradition going back to Egypt and beyond. After the Marys are returned to their chapel, the dancing and singing goes on late into the night as the crowds prepare for the third day’s bull fights, bandido runs and parties in honor of the Gypsy benefactor, Folco de Baroncelli.

These celebrations mark a fountainhead. Like the spring in the church of the two Marys, one of many miraculous springs we will find along the way, these traditions serve as a source point for the broad esoteric current that King Rene himself labeled the underground stream of lost Arcadia. And with this knowledge — the mystery hidden in plain sight, known to the Gypsies and the common folk — the true history of that underground stream, the Gnostic Christianity of the west, can be traced through the centuries.

* * * * *

Among the many traditional images used to describe this underground stream, that of grafting vines and growing grapes, the viticulture and alchemy of wine-making, has an unusual prominence. Standing in the midst of the vinyard planted by Nostradamus’ grandfather, Jean de St. Remy, at the Chateau Roussan, not far from the Roman city of Glanum, it is easy to see in this grafting of vines, the grafting of cultures, from Egyptian to Celtic to Greek to Hebrew, which finally produced the fruit of Gnostic Christianity and the wine of the medieval esoteric wisdom. On the land, the metaphor has a meaning rooted in the mythology of its history. In the course of an afternoon’s drive, from St. Remy to the sea, one can visit the monuments, hidden in plain sight, of this esoteric history. However, to find these monuments and understand their significance, we will need the guidance of the 20th century’s most enigmatic astro-alchemist and hermetic philospher, the inscutably anonymous Fulcanelli.

In order to follow Fulcanelli’s guidance, we must first understand something of his methods. In his masterpiece, The Mystery of the Cathedrals, Fulcanelli presents a series of images, drawn mostly from Notre-Dame de Paris, which, at first, seem to be a whimsical or even chaotic deluge of allusions and interconnections. Only when this pattern is correctly seen as an attempt to present a specific interpretation of the cabalistic Tree of Life does the apparent chaos resolve into the masterly order of the hermetic grand theme. This grand theme is then augmented by the juxtaposition of symbols from other places, such as Amiens, and the group of images drawn from private houses in late 15th century Bourges. This system of symbolic juxtaposition, reveals, in ways not unlike that of surrealist art, deeper meanings behind the emerging symbolic construct. It is almost as if Fulcanelli, the master symbolist artist, had inadvertently stumbled onto the magic secret of surrealism. Or, more likely, surrealism is merely the latest artistic expression of a hermetic world view stretching back into the myths of antiquity.

Almost every commentator on Fulcanelli’s work agrees that the explanation of the “Green Language” given in chapter 3 of part one of MotC is the heart of the book. It is the concept that you must grasp in order to have any chance at understanding (the sephiroth attributed to its location in the Tree of Life is Binah, or Understanding) the rest of the book. However, even this basic component seems to have been greatly misunderstood by Fulcanelli’s critics and interpreters. Few, apparently, have focused on just what it was that Fulcanelli actually said about the art gothique.

The first two chapters of MotC contains Fulcanelli’s personal connections, interwoven with a wealth of obscure clues that only become significant in retrospect. These chapters place Fulcanelli in the somewhat old-fashioned, for 1926, position of a Victor Hugo romanticist longing for the good old days of the Middle Ages. Chapter two ends with the declaration that not only are the cathedrals books in stone, and Notre-Dame in particular is the Philosopher’s Book, but that the book has secrets hidden, as Fulcanelli so eloquently says, “under the petrified exterior of this wonderous book of magic.”

Fulcanelli begins chapter three by stating that “it is necessary for me to say a word about the term gothic as applied to French art, which imposed its rules on all productions of the Middle Ages and whose influence extends from the twelfth to the fifteenth century.” Fulcanelli suggests that Gothic does not refer to the ancient Germanic tribe, or to a term of derision used by faux-classical elitists in the 18th century, but to a hidden, cabalistic, meaning that resists even the attempts of the artistic establishment, The French Royal Academy, to apply the more architecturally correct term of ogival art to the productions of the High Middle Ages.

So far so good. We are still firmly in the grip of Hugoesque romanticism. But Fulcanelli’s next paragraph marks a line in the sand across which lies the fairyland of the occult. We cross it so softly that most commentators have never even noticed it. “Some discerning and less superficial authors, struck by the similarity between gothic and goetic, have thought that there must be a close connection between gothic art and goetic art, i.e. magic.” Leaving this tantilizing statement hanging in the aethyrs, Fulcanelli doesn’t dispute the attribution, but plunges on to what, for him, is the heart of the matter.

“For me,” Fulcanelli tells us, “gothic art (art gothique) is simply a corruption of the word argotique (cant), which sounds exactly the same.” From this, he determines that “a cathedral is a work of art goth or of argot, i.e. cant or slang.” This phonetic, spoken cabala is the same as the puning slang common to all languages and used by all outsiders to mask their communications from the Others. Again, so far so good. Fulcanelli is on solid literary and linguistic footing with this supposition. But with his next sentence, which gives us an example of how the cant works, Fulcanelli points to the core of the mystery.

“The argotiers, those who use this language, are the hermetic descendents of the argonauts, who manned the ship Argo. They spoke the langue argotique — our langue verte (green language or slang) — while they were sailing towards the felicitous shores of Colchos to win the famous Golden Fleece.” Fulcanelli then adds a common expression current in Paris in the ’20s about intelligence and the use of slang, and continues: “All the Initiates expressed themselves in cant; the vagrants of the Court of Miracles — headed by the poet Villon — as well as the Freemasons of the Middle Ages, ‘members of the lodge of God,’ who built the argotique masterpieces, which we still admire today. Those constructional sailors (nautes) also knew the route to the Garden of Hesperides. . .”

He then adds a paragraph about how only outsiders use and understand cant in our day (in which he takes a swipe at the then-current nobility), and ends the paragraph with the observation that art got is really the art of light. He follows this up with a long paragraph of Gnostic philosophy, before finally returning to his theme of the secret language. Here, he labels it the Language of the Birds, “parent and doyen of all other languages — the one spoken by philosophers and diplomats.” Fulcanelli continues that this was “the language which Jesus revealed to his Apostles, by sending them his spirit, the Holy Ghost.” Fulcanelli declares that “this is the language which teaches the mystery of things and unveils the most hidden truths.”

Immediately on the heels of that revelation, comes two sentences linking the whole concept with the Inca. “The ancient Incas called it the Court Language, because it was used by diplomats. To them it was called the double science, sacred and profane.” He then goes on to place the language with its medieval equivalents, The Gay Science, the Gay Knowledge, The Language of the Gods and a referrence to Rabelais’ Dive-Bouteille, before assuring us that it was the language spoken before the fall of the Tower of Babel. He ends the paragraph by noting that apart from the principles of cant, or slang, traces of the Green Language can be found in the dialects of Picardy and Provence, and “in the language of the Gypsies.” He then ends the chapter with one more classical allusion, that of Tiresias who gained his knowledge of the language of the birds from Minerva/Athena and shared it with the ancient philosophers Thales, Melampus and Appolonius of Tyana.

What are we to make of this chapter?

If it is the key to any further understanding, then we must make an effort to understand what Fulcanelli is telling us. He starts by saying that this punning slang is cabalistic, that it is a pattern of symbolic significance. He then adds that it is also a magical, goetic, art. He emphasizes the phonetic connection to argot, cant or slang, then links it to the Argonauts of the quest for the Golden Fleece by insisting that the Green Language was spoken by the crew of the Argo as it sailed “towards the felicitous shores of Colchos.” He suggests that the language of this quest is the foundation of all initiation, “All Initiates expressed themselves in cant.” In the same sentence he links this idea with the Court of Miracles of the troubadour poet Villon and the artists who built the cathedrals, impling that these groups were somehow the same nautes, or sailors, as the Argonauts.

By any standard of comparision, this is an unusual collection of allusions and assertions, even for a hermetic author. Fulcanelli seems to be telling us, as plainly as possible, that the medium is the message. The argot is the art of light, the core of a Gnostic philosophy expounded so eloquently by Fulcanelli in the paragraph which comes immediately after the art of light statement. “Language,” Fulcanelli tells us in that passage, “the instrument of the spirit, has a life of its own — even though it is only a reflection of the universal Idea.” This Gnostic meta-linguistic mysticism is the core not only of alchemy, but of illumination itself.

Fulcanelli understood this, as he shows when he states that argot, the initiation of the Argonauts, is but “one of the forms derived from The Language of the Birds.” This Ur-language, Fulcanelli insists, is the common language of initiation and illumination behind cultural expressions as different as the Christian, the Inca, the Medieval troubadors and the ancient Greeks. And traces of it can be found in the dialects of Picardy and Provence, and most important of all, in the language of the Gypsies.

We are left stunned, convinced that Fulcanelli has just told us that the western cabala used by the troubadors and the builders of the cathedrals is based on the language of the Argonauts and the quest for the Golden Fleece. Which in turn is but one application of a vast Ur-language of symbols that unite the global cultures of mankind, from the Inca to the ancient Greeks. And, to top it off, he told us that traces of it can be found in the language of the Gypsies, a fairly obvious reference to the Tarot, long held to be a Gypsy invention.

However, our understanding is not in error. In fact, it might just be the best interpretation possible for this pivotal chapter in Mystery of the Cathedrals. Fulcanelli, at the very beginning of his masterpiece, has told the careful reader the key to the mysteries left to unfold. While we may understand the gist of what Fulcanelli is saying — the idea of a secret language or code is not hard to fathom in hermetic works of this nature — we risk missing the key point, the Argonauts. It is only toward the end of MotC that Fulcanelli explains his mysterious insistence on the legend of Jason and the Golden Fleece. The careful reader, however, will have figured out from this chapter that the images in the book should be arranged according to a basic symbolic Tree of Life pattern. This is in fact the simple secret that unlocks the mystery that Fulcanelli is attempting to elucidate.

Once this Tree of Life pattern is built up from the images at Notre-Dame and Amiens, with a few extra additions from St. Chapelle, St. Victor and elsewhere, an understanding of the basic process of astro-alchemy can be gleaned. This is the real secret, and from Fulcanelli’s point of view there is no mystery about it. But once this secret is revealed, Fulcanelli goes on to propose a three-in-one, triple mystery that neatly ties the historical, mythological and cosmological elements into one coherent framework.

This new Tree of Life, like the mystery itself, grows out of Bourges in Berry. Fulcanelli ignores the town’s Gothic cathedral, with its stunning apocalyptic stained glass, and concentrates on two contemporaries of Good King Rene in the mid 15th century, Jacques Coeur and Jean Lallemant, and their houses. This is a significant departure; up to this point Fulcanelli has focused exclusively on cathedrals. This departure signals the shift from the theoretical to the operational.

Fulcanelli is pointing us toward a moment in the late 15th century when the underground stream broke the surface of history. He suggests that the mystery of Bourges is the mystery of the esoteric current in the ancient past, the present of the 15th century, and the future down to and beyond the 20th century. The mystery of initiation encompasses a vast reach of time, Fulcanelli insists, but the strands of the tapestry emerged into a pattern at Bourges in the mid1400’s.

Fulcanelli directs our attention toward eight images in the two houses. Two are from Jacques Coeur’s house, and six from Lallemant. They can be analysed as two images that establish both individuals as alchemists, the Scallop Shell and the Vessel of the Great Work, three historical and mythological themes, Tristan and Isolde, The Golden Fleece and St Christopher, and three initiatory images from the inner sanctum of Lallemant mansion, the pillars, the ceiling and the credence of the chapel.

Even this simple pattern reveals groups of threes within threes. The first of the three groups of symbols shows us that Jacques Coeur was a pilgrim, a fellow traveler, but Jean Lallemant was the operating agent with the vessel of the great work. The role of grand master, however, is undefined. We are left with the impression that a third personality exists, made conspicuous by its absence. Who was he?

The next of the three groupings reinforces this impression. Here we are met with three narrative images, symbolic stories balanced on that fine line between history and mythology. There is a core of reality to these tales, even when we are aware of their mythological elements. But, on the surface, there is nothing to connect the love story of Tristan and Isolde with the ancient Greek legend of the Golden Fleece, and both seemingly have nothing in common with the Christian legend of St. Christopher and the very heavy Christ-Child. And yet, Fulcanelli presents the simple but overwhelming evidence from their own houses that these masters of the subtle art, the Green Language itself, placed the utmost importance on these three myths. What do these three stories have in common?

Of course, the third mystery grows out of the first two: Just what were these initiations designed to reveal?

The answer to that is the ultimate secret, the secret of time itself. In the 2nd edition of MotC, Fulcanelli provides the solution by adding a chapter on the Cyclic Cross of Hendaye. These three images, added to the eight of Bourges, complete the Tree of Life, including Daat, gnosis or knowledge. This last group of three reveals the cosmological underpinings of the entire hermetic philosophy of astro-alchemy. The final image in the group, the Tympanum of St. Trophime at Arles, completes the circle, both symbolically and on the ground, returning us once again to the ancient city of the Argonauts.

This three-fold pattern is reflected in the design of the whole book. The first secret, that of the Tree of Life, is formed from the sword in the stone pattern of the nine chapters in part one. They form a framework for the sephiroths which is then amplified and deepened by the images from Notre-Dame. To this is added the third level, the planetary seals from Amiens cathedral. The next three-fold pattern is the mystery of Bourges outlined above. The last grouping of three is the three interlocking cycles of the Hendaye Cross, their symbolic reflection on the cathedral at Arles, and finally the three dragon axis in the sky which form the triple alignment of the Great Galactic Cross.

This compounding of threes, 3 x 3 x 3, or 3 cubed = 27, presents us with the key number in the precessional cycle, the core of the secret hidden behind the Christianized INRI, whose letters in Hebrew add up to 270. From this brief explication of the mystery at the heart of the Mystery of the Cathedrals, it is possible to glimpse the genius and coherence of this very guarded and hermetic masterpiece. The message is the medium, language contains its own gnosis, and initiation truly is, as the Grail legends declare, the ability to ask the correct questions.

As we unravel the triple weave of this hermetic tapestry we will discover the answer to all of our questions, and in doing so experience a glimpse of a very different reality. Fulcanelli, whoever he was, wrote as the last initiate. Not as the one who puts the light out as he leaves, but as the one who makes sure that the eternal flame is burning brightly in some lost corner of Plato’s cave. What we have discovered in the course of this book, of our own past, our spiritual heritage and the hope of human evolution, is due to his guidance and insight. Without the help of someone who knew, and could prove it, the mystery might never have been unveiled.

* * * * *

In unveiling the mystery, we have chosen to follow the master’s design.

Part One reveals the theoretical underpining of the symbolic cabala as presented by Fulcanelli’s choice of images from Notre-Dame and elsewhere. This Tree of Life, built from the sword in the stone of the initial chapters, the full tree from Notre-Dame and the planetary seals from Amiens, provides us with an overview of the symbolic process out of which the next two levels unfold.

Part Two examines the questions of history and mythology presented by the images from Bourges. From the answers to these question arise a vast untold story of the underground stream in the west, from Jason and the Argonauts to the Gnostic Christians, the Cathars and the legends of the Holy Grail, down to the true identity of the Knights of the Rosy Cross.

Part Three examines the cosmological questions raised by the inclusion of the Hendaye chapter and reveals that the inner secret of astro-alchemy is the secret of the end of time, Fulcanelli’s double catastrophe. The symbols shown on the Cyclic Cross of Hendaye will lead us, by methods already shown to be a crucial component of the overall mythology, to the conclusion that a galactic level event is about to occur. A conclusion that is supported by the latest scientific evidence, which incidently provides suggestive clues to the nature of the astro-alchemical process.

Having revealed the mystery at the core of Fulcanelli’s message, an Epilogue brings us back to the lost Roman city of Glanum, where the prophecies of Nostradamus and the artwork of Leonardo Da Vinci combine to point us toward the final proof, the alchemical tomb of the “Mansol,” St Jean de Luz, the Son of Jesus, and the true Gnostic savior.

More Articles from Sangraal.com:

Submit your review | |